Minh Phuong Vu, ANU , for East Asia Forum

In March 2023, China and ASEAN resumed negotiations on the South China Sea (SCS) Code of Conduct, which aims to reduce the risk of conflict in the disputed maritime zone. But such progress has not calmed the situation. In February 2023, the Chinese Coast Guard harassed a Filipino Coast Guard crew with a ‘military-grade’ laser, sparking an intense response from Manila.

Vietnam has been comparatively quieter, but silence does not mean that all is well. On 25 March 2023, a Chinese Coast Guard vessel sailed near oil and gas wells belonging to Vietnam’s Vanguard Bank, resulting in a dangerous encounter between Chinese and Vietnamese patrol boats.

Given Beijing’s ongoing efforts to assert greater control in the SCS, states like Vietnam and the Philippines are seeking greater support from external partners to help resist China’s grey zone activities. In March 2023, the Philippines joined a three-way security framework with Japan and the United States to counter China’s growing assertiveness in the Indo-Pacific.

This raises questions about the direction of Vietnam’s maritime cooperation with its key partners as Vietnam adheres to a non-alliance principle, which limits its involvement in formal and informal military coalitions. But Vietnam can still develop security relations that contribute to its defence capability.

Hanoi recognises the importance of fostering maritime cooperation with capable partners like the United States, India and Japan to deter Chinese escalation in the SCS. But not all these relationships have equal growth prospects and Hanoi may prefer advancing some ties over others.

The 2014 Chinese oil rig crisis in Vietnam’s exclusive economic zones pushed Vietnam to strengthen its cooperation with Washington, who subsequently removed its ban on non-lethal weapon sales to Vietnam. These security ties have since grown, with Washington transferring two refurbished US Coast Guard Hamilton-class cutters to Vietnam.

In 2018, Vietnam participated in the Rim of the Pacific Exercise (RIMPAC) for the first time and welcomed the first port visit by a US aircraft carrier in over 40 years. Maritime security has also become a key feature of their annual US–Vietnam Political, Security and Defense Dialogue.

But other considerations have dampened expectations of greater maritime cooperation.

China–US competition is intensifying and may manifest in a conflict over Taiwan. Conscious of its geographical proximity to and economic reliance on Beijing, Vietnamese leaders are cautiously navigating their relationship with Washington. In 2022, Vietnam did not participate in RIMPAC and cancelled two port calls by US aircraft carriers, reportedly due to Vietnam’s ‘concerns about a possible Chinese attack on Taiwan’.

Vietnam’s lack of political trust in the United States could further limit cooperation. Washington’s continuing promotion of democracy in its Indo-Pacific strategy could irritate Hanoi. Its distrust has deepened since the Trump administration withdrew from the Trans-Pacific Partnership and accused Vietnam of currency manipulation. Vietnam has avoided major US weapon purchases and US aircraft carriers have not been allowed to dock near Vietnam’s main naval base at Cam Ranh Bay.

Compared to its hesitancy over maritime cooperation with the United States, Hanoi appears more comfortable with India and Japan. Like the US, India and Japan are concerned about China’s activities in the SCS but do not seek to unduly antagonise Beijing. Maritime cooperation with Tokyo and New Delhi allows Vietnam to keep enough distance from the United States to avoid upsetting Beijing while still maintaining its maritime security.

A higher level of trust also makes India and Japan attractive partners for Vietnam. A shared principle of non-alignment provides a solid foundation for cooperation with India, while Japan’s credibility is unmatched due to its role in facilitating Vietnam’s economic modernisation.

Maritime cooperation with India and Japan has strengthened significantly over the past decade. In 2014, New Delhi provided US$100 million credit to help Vietnam build 12 high-speed patrol boats that were delivered in 2022. In 2015, Tokyo transferred six used vessels to the Vietnam Fisheries Resources Surveillance force.

In 2016, India again offered Vietnam US$500 million credit for a larger-scale defence procurement, which will be finalised soon. In 2020, Japan provided funding for six Aso-class patrol boats and a satellite-based surveillance system, which would enhance Vietnam’s domain awareness and law enforcement capability. Additional Japanese defence equipment and technology exports to Vietnam are expected following a 2021 agreement.

Maritime cooperation with India and Japan also includes dialogues, naval exercises, ship visits and joint training programs. Since 2018, Vietnam and India have carried out bilateral maritime exercises in the SCS and Indian warships have regularly visited Vietnam’s ports. Vietnam has also conducted several low-key joint exercises with Japan. These enhance interoperability between navies and coast guards on a range of issues, such as unplanned encounters, antipiracy, illegal fishing and disaster relief.

Vietnam’s maritime cooperation with India and Japan has grown significantly in the face of challenges from China, while engagement with the United States has been more selective. Although recent US efforts to reengage Hanoi signal that US–Vietnam maritime cooperation will not stall forever, fear of antagonising China and a lack of trust will continue to limit cooperation.

India and Japan — as capable and willing partners — provide a solution for Hanoi to keep a safe distance from Washington, while still securing external support to build up its maritime capacity.

The original article can be found here at East Asia Forum.

Minh Phuong Vu is PhD candidate at ANU Coral Bell School of Asia Pacific Affairs researching the South China Sea.

This article is part of the ‘Blue Security’ project led by La Trobe Asia, University of Western Australia Defence and Security Institute, Griffith Asia Institute, UNSW Canberra and the Asia-Pacific Development, Diplomacy and Defence Dialogue (AP4D). Views expressed are solely of its author/s and not representative of the Maritime Exchange, the Australian Government, or any collaboration partner country government.

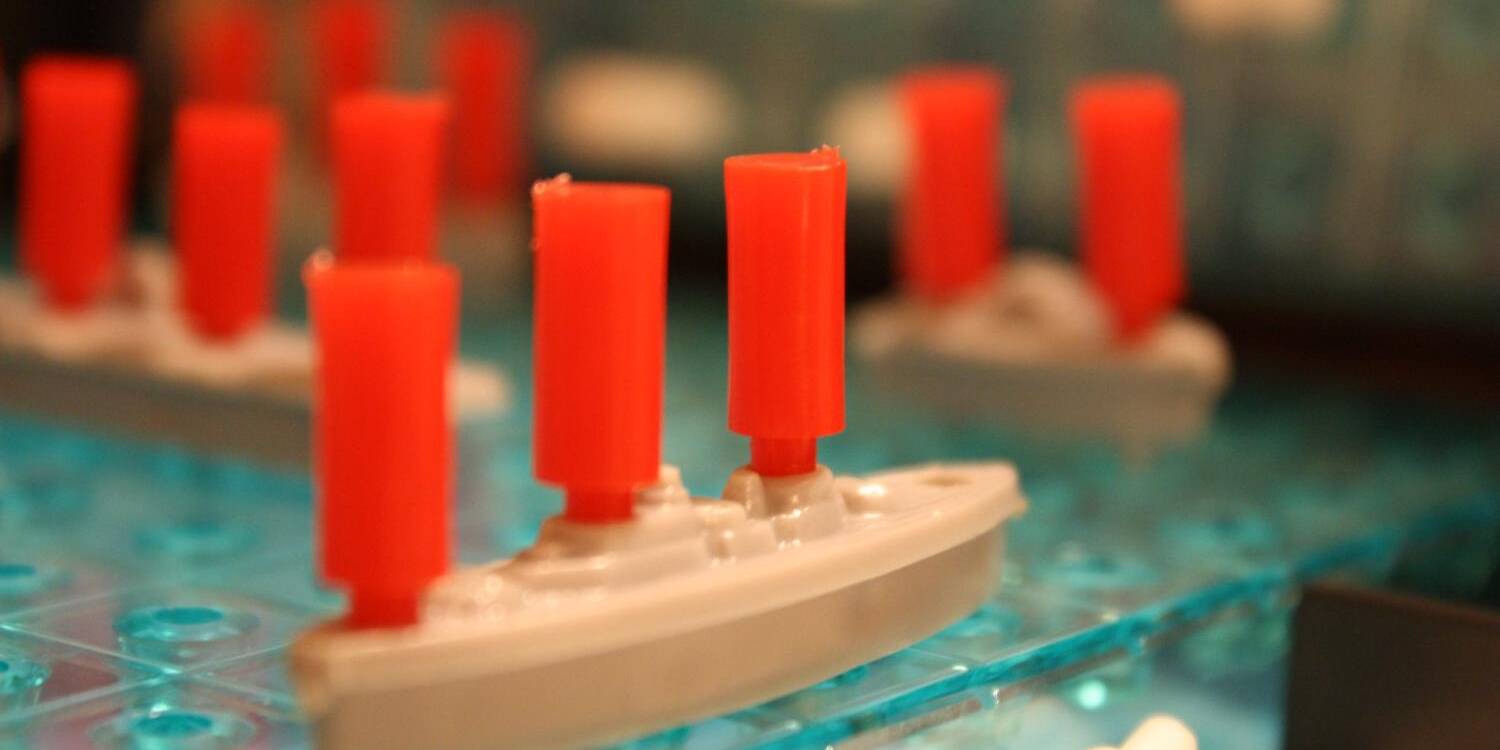

Feature Image: VPN’s Frigate HQ 016 Quang Trung in the Second Edition of Indian Navy-Vietnam Peoples’ Navy Bilateral Exercise 2019/ via Wikimedia Commons

Related Analyses

September 15, 2024

West Philippine Sea: Several factors force BRP Teresa Magbanua to return – PCG

0 Comments1 Minute