Tom Barber and Melissa Conley Tyler, for ASPI The Strategist

Maritime security is a term that can mean almost anything.

For many, it conjures images of big-ticket ‘hard security’ issues like military modernisation, island-building, freedom-of-navigation operations, maritime surveillance, grey-zone tactics and maritime militia.

But maritime security also encompasses myriad other topics like illegal fishing, piracy, terrorism, energy, trade, international law, irregular migration, biosecurity, climate change, telecommunications, transnational crime and cyber. In the case of sea-level rise, security is sought from the encroaching maritime domain itself.

Without a uniform Australian definition of maritime security, exactly what the concept means is subject to the interpretation of the 25 federal departments and agencies with maritime responsibilities and objectives. Australia’s current approach is based on compartmentalisation, with government bodies’ conception of maritime security (and the ways they pursue it) being a function of their context.

Bureaucratically speaking, there’s an understandable appeal in tackling maritime security in this siloed way given its numerous facets. But a consequence of this approach is that, rather than one overarching document, Australia’s maritime security priorities and objectives are dispersed across several discrete strategies.

The 2022 Australian government civil maritime security strategy articulates some of Australia’s maritime security objectives. These include upholding sovereignty and freedom of navigation, protecting maritime infrastructure and natural resources, protecting maritime domain users, supporting the rules-based order in accordance with international law, and strengthening relationships in the region. But as a civil strategy, much is intentionally left out.

The recent defence strategic review outlines the military aspects of Australia’s maritime security calculus, identifying the nation’s maritime approaches as primary to its defence and warning that an ability to secure them is critical. But as a military planning document, its focus is understandably on the defence aspects of the maritime domain.

In a more contested strategic environment, there’s an increased need for all elements of Australian statecraft to work together. Australia’s compartmentalised approach has an obvious gap in the lack of a single strategy that brings the many strands of maritime security together.

A recent paper looking at how Australia can coordinate with Southeast Asian countries on maritime security outlines the benefits of developing a national strategy.

It recommends that Australia set out its national interests and communicate its priorities in the region through a clearly articulated national maritime security strategy for the Indo-Pacific. A publicly declared strategy would provide an overarching framework to bring the various arms of the Australian government together. Expressing a whole-of-government maritime security vision would foster a coherent interdepartmental approach to challenges in the region. It would also be an important element of transparency for Australia’s relationships in the region.

Such a strategy wouldn’t require all government departments and agencies to have the same operational goals, or need every aspect of international engagement to be fully integrated. Rather, it would provide high-level, strategically coherent guidance, ensuring the different aspects of Australian statecraft pull broadly in same direction.

Relatedly, while the ambiguity of having no official definition of maritime security can be beneficial insofar as it allows room for manoeuvre, it can also mean different bureaucracies take maritime security to mean different things, in some cases undermining Australian statecraft by wasting resources on duplication, rubbing up against one another or even working at cross-purposes.

The value of signposting clear overall objectives would outweigh the benefits the current vagueness brings. A maritime security strategy that included an official Australian definition would therefore also be of benefit.

The maritime domain is simultaneously a threat and an opportunity; a conduit and a barrier. For an island nation like Australia, its centrality is a constant. As the 2017 foreign policy white paper bluntly states: ‘Australia’s own connections with the world will continue to rely on our sea lines of communication.’

With a multiplicity of issues that interact and overlap, the maritime domain is arguably the most complex and eclectic of all. This makes striving for coherence across different Australian maritime actors hard, but also more important. An overarching, clearly articulated Australian maritime security strategy will help in that respect, aligning departments and agencies behind common objectives and communicating Australia’s priorities abroad.

The original article can be found here at The Strategist.

Tom Barber is program manager and Melissa Conley Tyler is executive director at the Asia-Pacific Development, Diplomacy & Defence Dialogue (AP4D). This article draws on the AP4D paper What does it look like for Australia and Southeast Asia to develop a joint agenda for maritime security, produced as part of the Blue Security program. AP4D thanks all those involved in consultations.

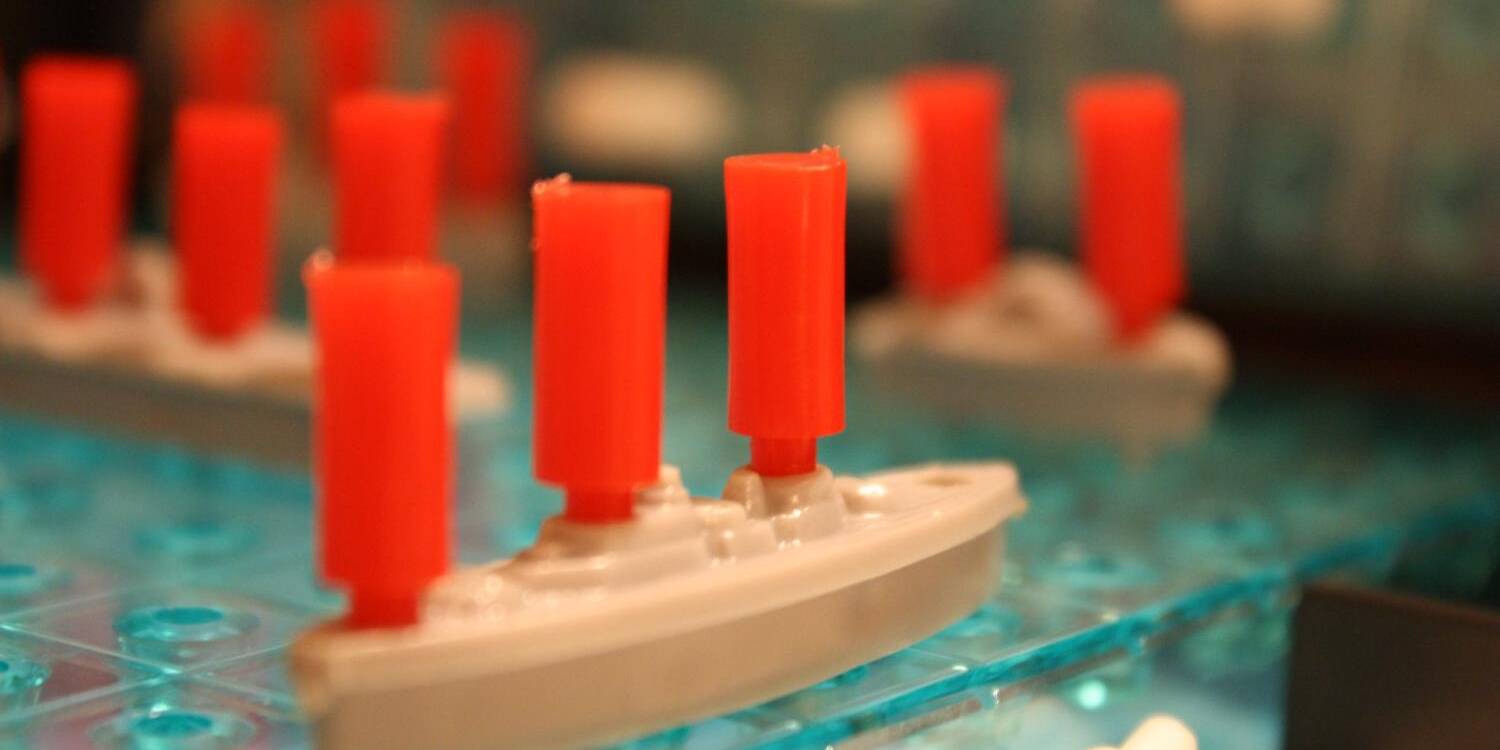

Feature Image: /via Australian Department of Defense

Related Analyses

September 15, 2024

West Philippine Sea: Several factors force BRP Teresa Magbanua to return – PCG

0 Comments1 Minute